Wild Waters:

Rivers, Lakes, Wetlands, Coast, and the Florida Wildlife Corridor

Governor’s House Cultural Center and Museum, St. Augustine

Opens September 1, 2025

Aiken Walker. Ocklawaha River, Sternwheeler. 1888. Harn Museum of Art, The Florida Art Collection, Gift of Samuel H. and Roberta T. Vickers

We invite you to experience our in-person exhibition at the Governor’s House in St. Augustine, Florida. Those visiting the exhibition can simply scan the QR codes displayed with the artwork to be directed to the detailed maps seen here. Below you will see selected segments of the exhibition text, followed by maps we designed to further enrich your understanding of the featured artworks and delve deeper into the detailed world of landscape conservation planning.

To see the exhibition in its entirety in person, make your way to the Governor’s House in St. Augustine, Florida!

Sunny beaches, exotic swamps, and winding rivers – these are the iconic Florida landscapes captured by the artists represented in The Florida Art Collection, a transformational gift from Samuel H. and Roberta T. Vickers to the Harn Museum of Art. Drawn exclusively from this collection, Wild Waters: Rivers, Lakes, Wetlands, Coast, and the Florida Wildlife Corridor showcases nearly forty paintings dated between 1871 and 1965 by more than 30 artists who were intrigued by Florida’s natural beauty. Travel across the United States and to Florida in the late 19th and early 20th centuries presented a significant challenge. By the mid-20th century, however, travel to Florida was booming due to new rail and highway networks – along with the availability of air conditioning. Although a few of the artists represented in Wild Waters lived in Florida, such as Franz Josef Bolinger, Harold Etter, and Buell Whitehead, most traveled from across the United States to capture the state’s natural beauty in their paintings. Additional artists featured include Maria a’Becket, Earl Cunningham, Sarah Harvey, Charles Robert Knight, Frank Henry Shapleigh, William Aiken Walker, and Mabel May Woodward.

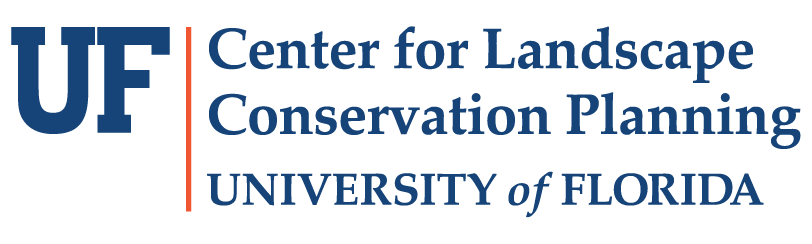

Wild Waters draws from The Florida Art Collection to spark conversations about how Florida’s natural environment has been represented historically and how it exists today, particularly within the Florida Wildlife Corridor, a statewide network of nearly 18 million acres of protected and unprotected wild and working landscapes. Water and land are deeply connected in Florida. With over 13.5 million acres of water, the state relies on its rivers, lakes, wetlands, and coastlines to support essential wildlife and habitat. This exhibition highlights the importance of water resources in Florida for maintaining natural communities as well as the economic, recreational, and other services that humans rely upon.

Wild Waters is organized by the Harn Museum of Art in partnership with the UF Center for Landscape Conservation Planning, and is guest curated by Eleanor A. Laughlin, Art and Museum Exhibition Coordinator at the Center for Landscape Conservation Planning.

GIS maps created by Elizabeth A. Thompson.

Rivers

Water and land are deeply interconnected in Florida. Our largest watershed, or area of land that channels rainfall and runoff to a common body of water, is the St. Johns River Basin, covering much of the eastern portion of the state from its southern headwaters in Brevard County to its mouth at the Atlantic Ocean, over 300 miles north in Jacksonville. This river basin provides a vital water supply for many cities and supports habitat for numerous fish, waterfowl, and terrestrial species, as well as state and federally listed species such as the Florida manatee. Rivers throughout the state support human recreation, and historically they were the best means of transportation to inland destinations before the railroad and highway systems. Several paintings in the exhibition depict rivers as they appeared prior to human interventions such as dredging and the imposition of dams and reservoirs. We see harbors prior to industrialization and wild rivers before housing developments encroached upon their banks. In contrast, a watershed-based planning approach adopts a conservation mindset, protecting upland areas and the waterbodies connected to them, safeguarding the state’s ecology, economy, and quality of life, all while conserving some of the natural beauty seen in these painted landscapes.

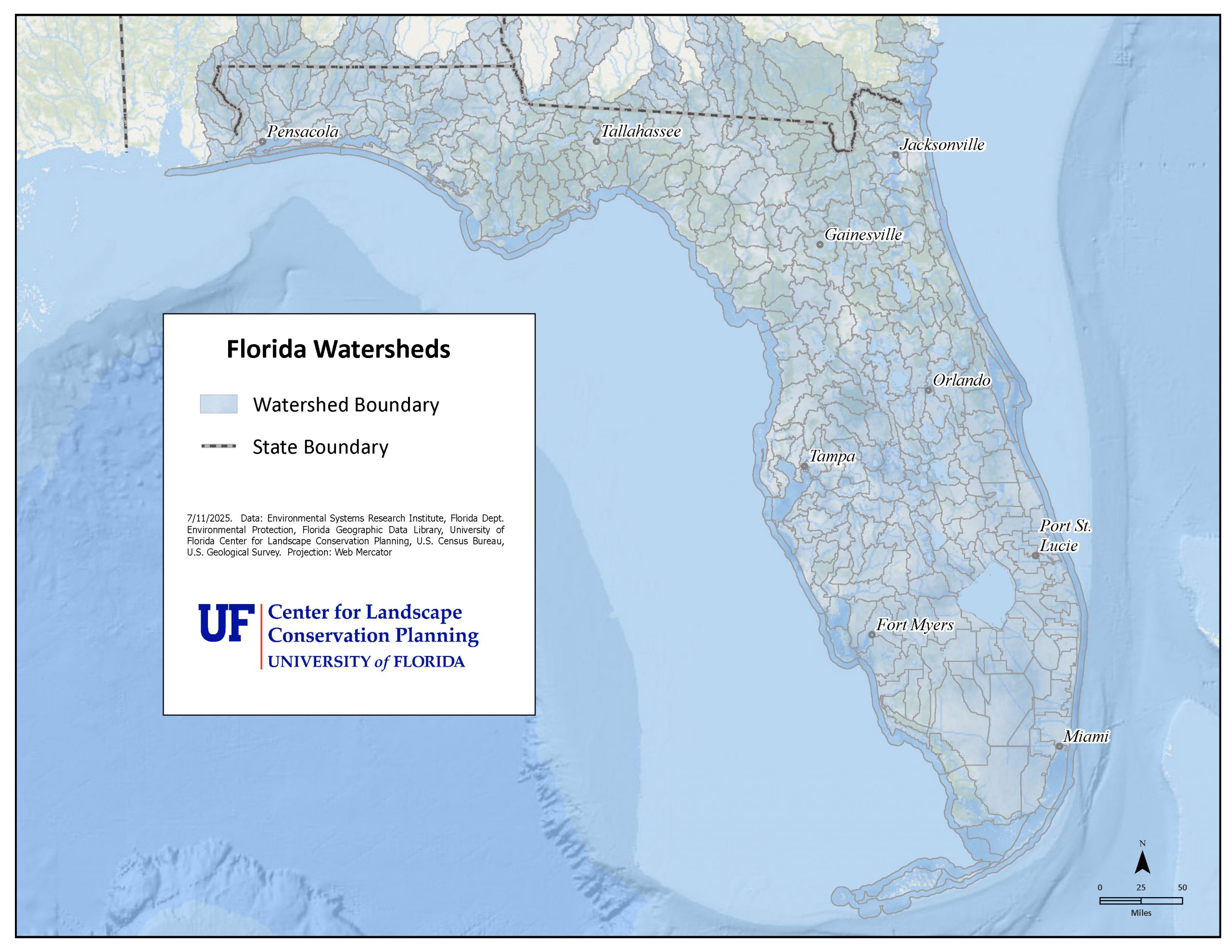

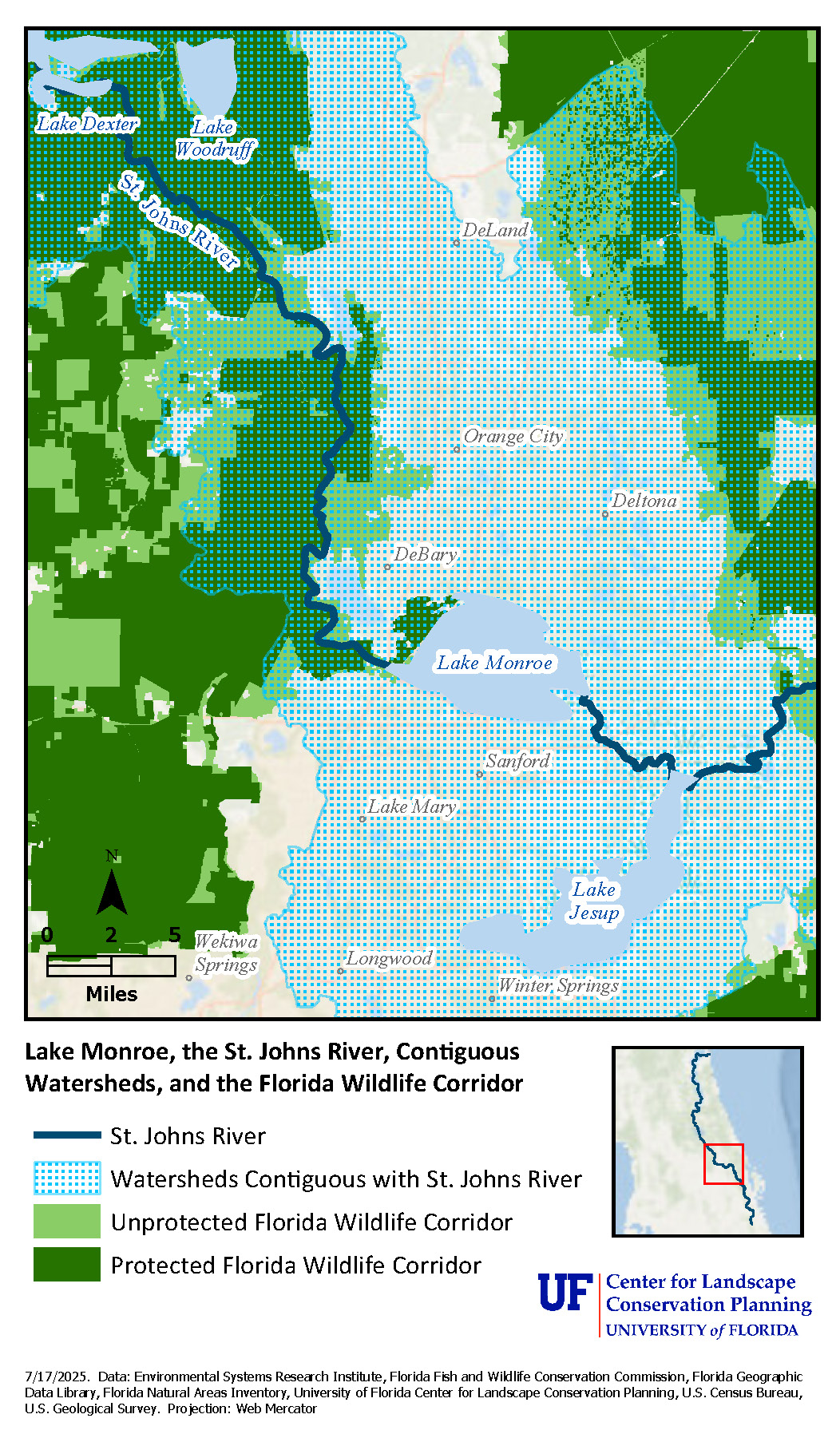

Map of the St. Johns River, Contiguous Watersheds, and the Florida Wildlife Corridor

The St. Johns River is one of the longest rivers in the United States, its watershed encompassing almost half of eastern Florida. Careful watershed-based planning is essential to protect upland areas and their connected water bodies downstream within the St. Johns River watershed, a river providing water supply for both Orlando and Jacksonville, habitat for numerous species , supporting key recreational and other water dependent industries, and multiple other ecosystem benefits.

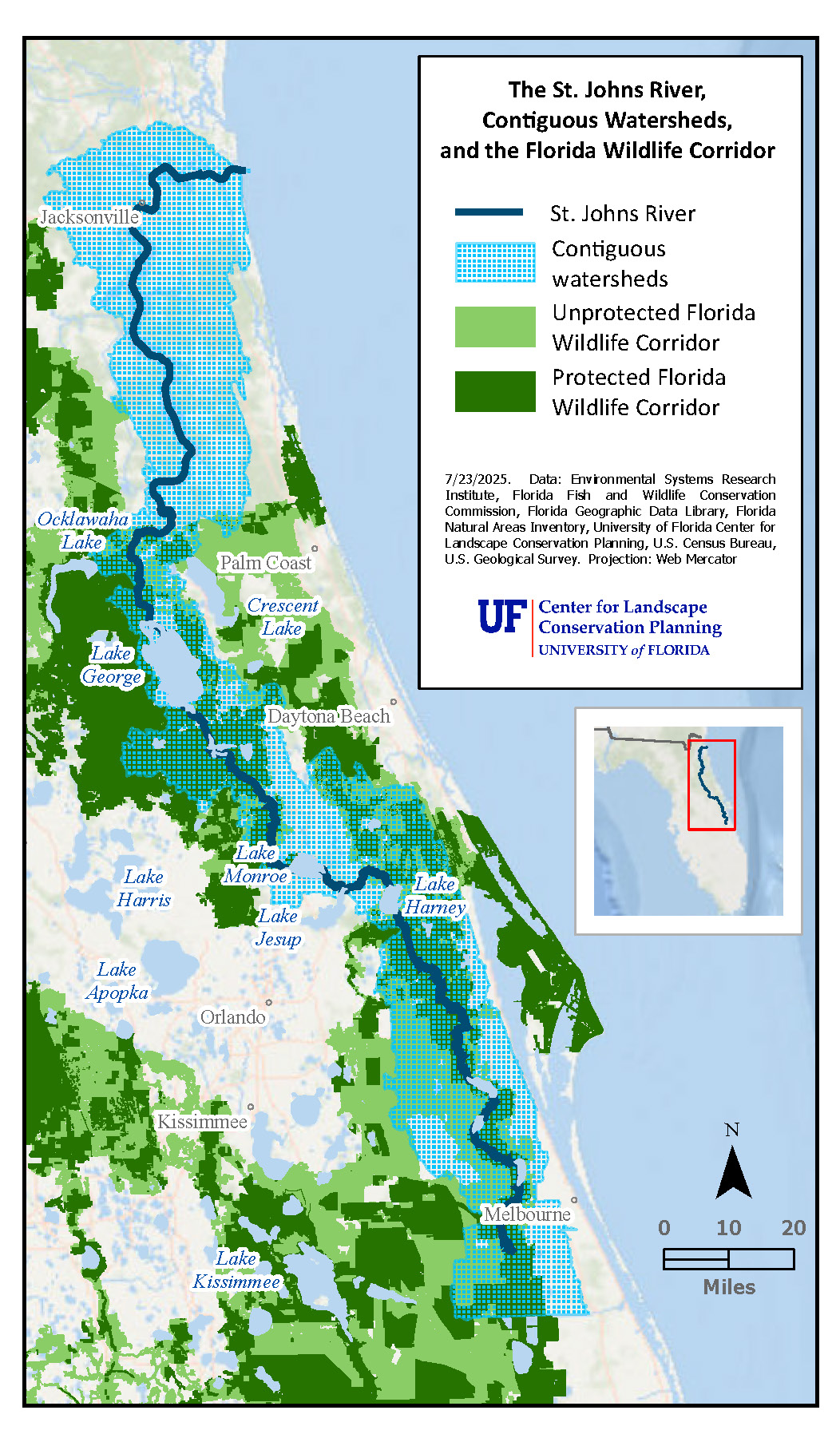

Map of the Caloosahatchee River, Critical Linkages, and Panther Priority Areas

The Caloosahatchee River is part of a critical linkage, or area of highest connectivity concern within the Florida Wildlife Corridor. The river flows through an area critical for agriculture and conservation, and careful management of the watershed is important for reducing flood risk and maintaining water resources for the City of Fort Myers and coastal estuaries. In the past, the Caloosahatchee River was traversable by the Florida panther, but has since been dredged for boat traffic, creating steeper, straighter banks. Now the width and depth inhibit panther movement, separating populations and impacting the movement of breeding females.

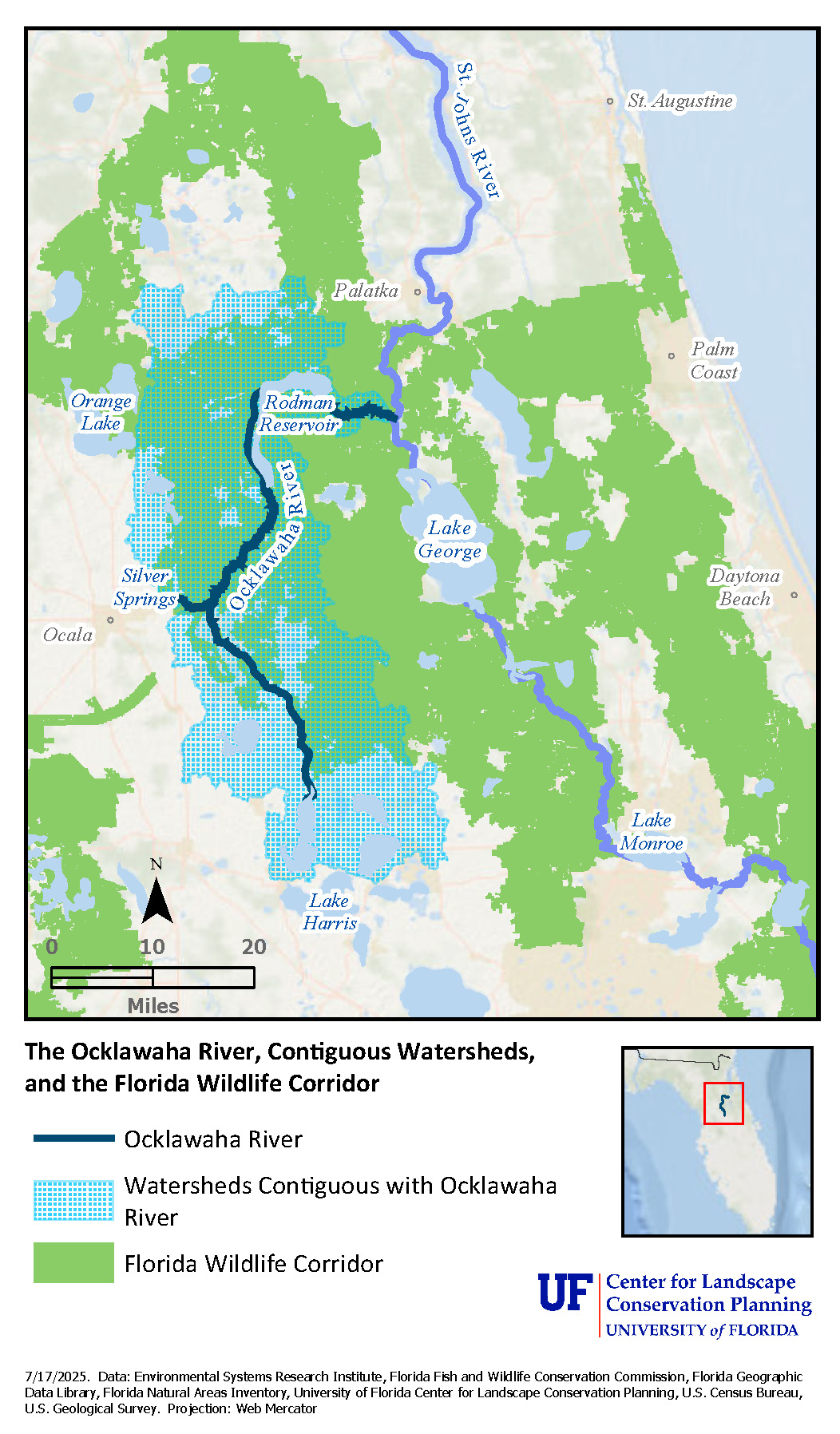

Map of the Ocklawaha River, Contiguous Watersheds, and the Florida Wildlife Corridor

The Ocklawaha River forms the western boundary of the Ocala National Forest and gave many nineteenth-century tourists spectacular views of the Florida wilderness from a comfortable seat. Today the Ocklawaha River has been altered by the Rodman Dam. The dam restricts the flow between three rivers: the Silver River, the St. Johns River, and the Ocklawaha River, significantly impacting water flows and resources within the watershed, and impeding movement of fish and other aquatic species, including the Florida manatee.

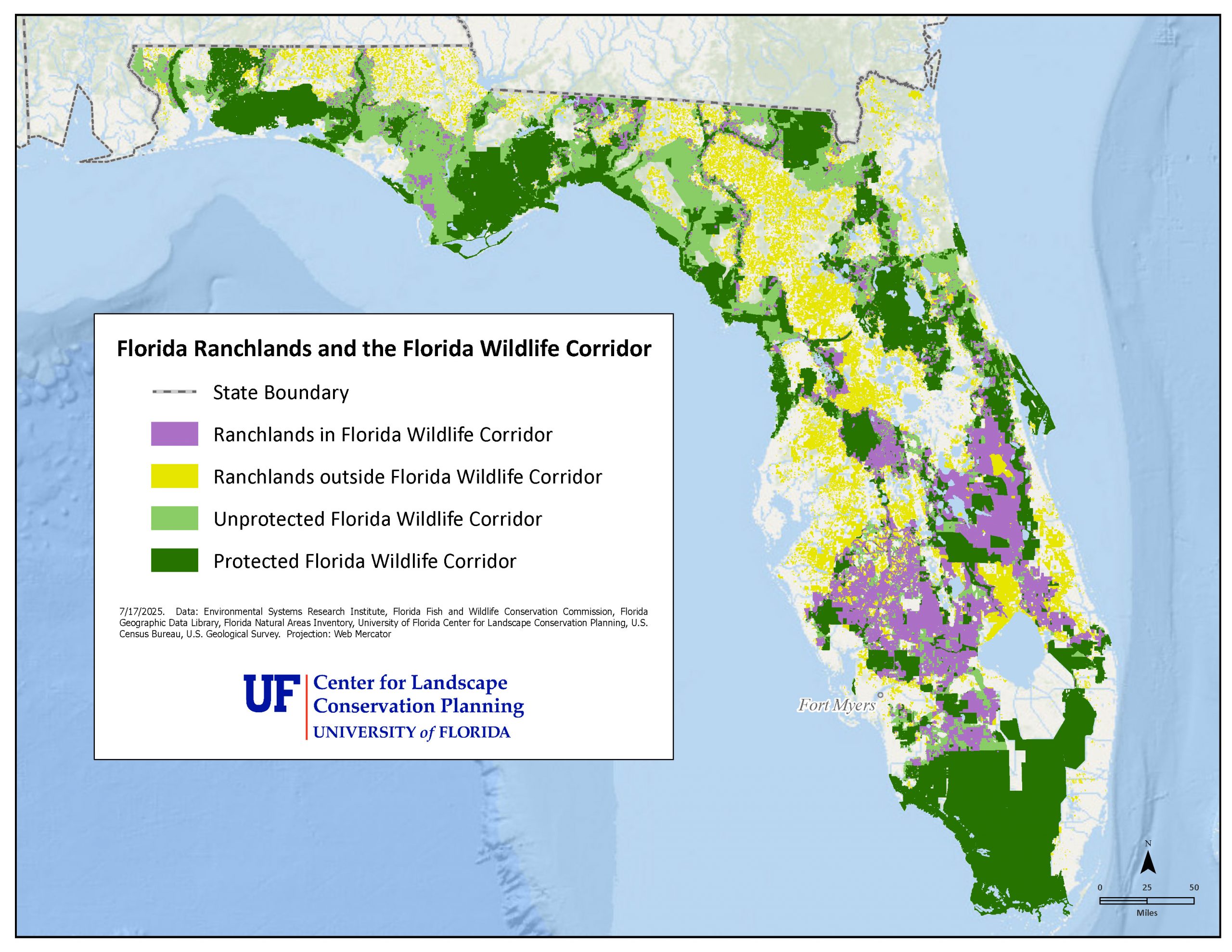

Map of Florida Ranchlands and the Florida Wildlife Corridor

Ranchers and rural landowners in southwestern Florida are essential partners in landscape conservation, with 80% of the remaining unprotected Florida Wildlife Corridor in agricultural land use. Although the agriculture and cattle industries are criticized for environmental impacts such as methane gas emissions, surface water runoff, and intensive use of water, the natural landscape it stewards provides critical benefits. When ranchers use best management practices, they are protecting water supply and quality, providing space for water storage in storms, supporting critical food production needs, supporting climate resilience, harboring wildlife, and promoting outdoor recreation. Ranching is part of our cultural heritage and an important path to a sustainable future for Floridians.

Lakes

Almost all of Florida’s lakes have been heavily impacted by human development, nutrient enrichment that causes hazardous imbalances, and the spread of invasive species. Pristine lakes are found only where the surrounding landscape is conserved. Most lakes (95%) in the state are already surrounded by development due to a preference for building houses near water. These developments are especially damaging since upland areas within watersheds are important for water recharge and filtration. Stormwater runoff from developed areas is a key source of nutrient, bacterial, and other contaminants.

Florida features a predominance of shallow, flatwater lakes formed when a river flows into a broad, flat plain, causing the water to redistribute over more surface area. The widening bank causes the river’s current to slow but not cease. Therefore, some of the waterbodies we call “lakes” are actually wide, flat rivers flowing very slowly. These water bodies are important for water storage during storms; water filtration by wetlands along their edges; habitat and hydration for a variety of species; and for human recreation. Additionally, lakes and ponds can be ephemeral or permanent. Ephemeral ponds in the panhandle are important for multiple focal species including federally and state listed species, such as the flatwoods salamander.

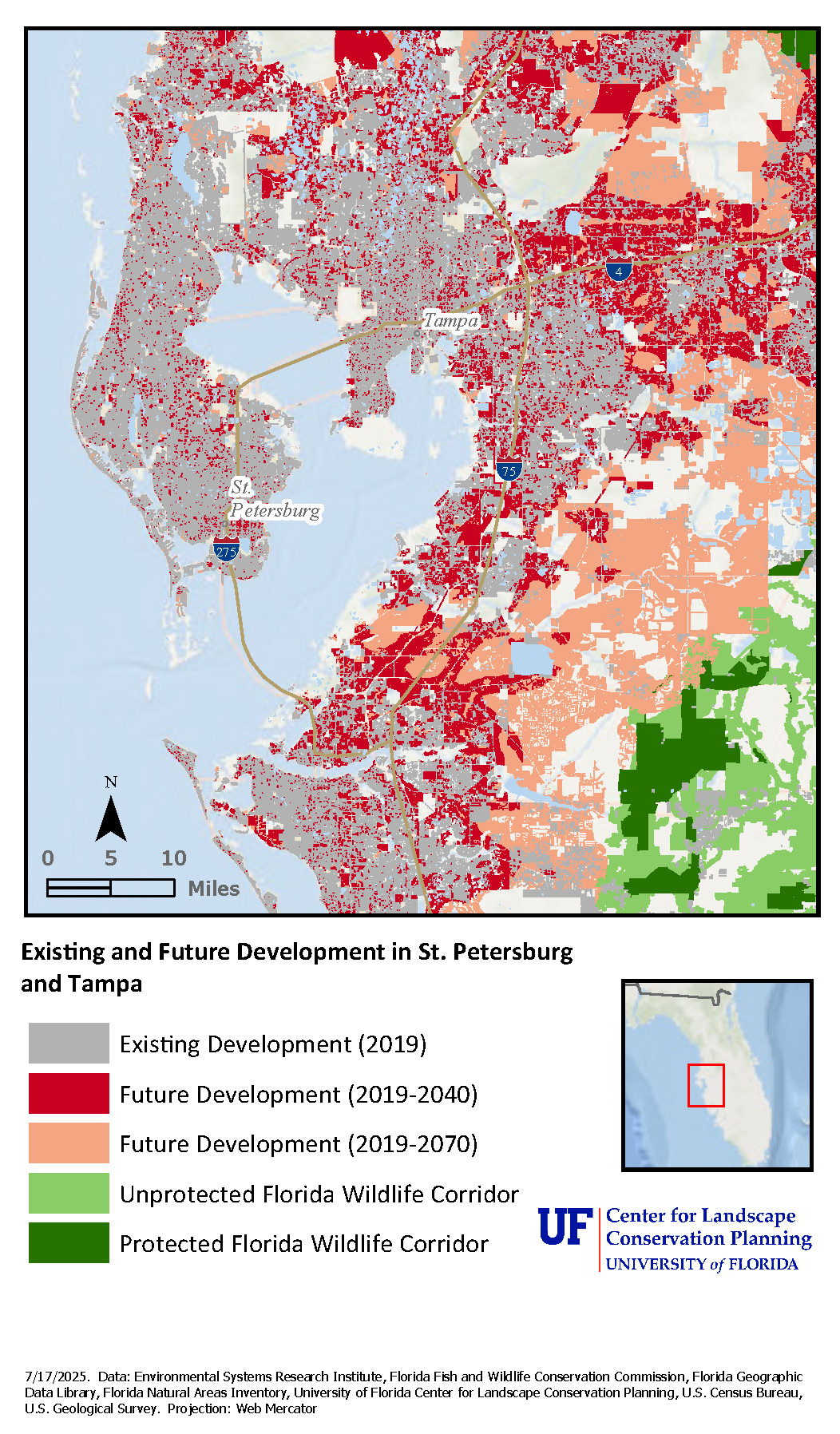

Map of Existing and Future Development in St. Petersburg and Tampa

Due to the urbanization of the St. Petersburg area, it is difficult to identify the precise location of the spring that inspired one of the nineteenth-century paintings in the exhibition. Land use, development, and water-related impacts have changed significantly within the region since this painting was completed. Unfortunately, developed landscapes are practically irreversible – once the landscapes they replace are lost, they are gone forever.

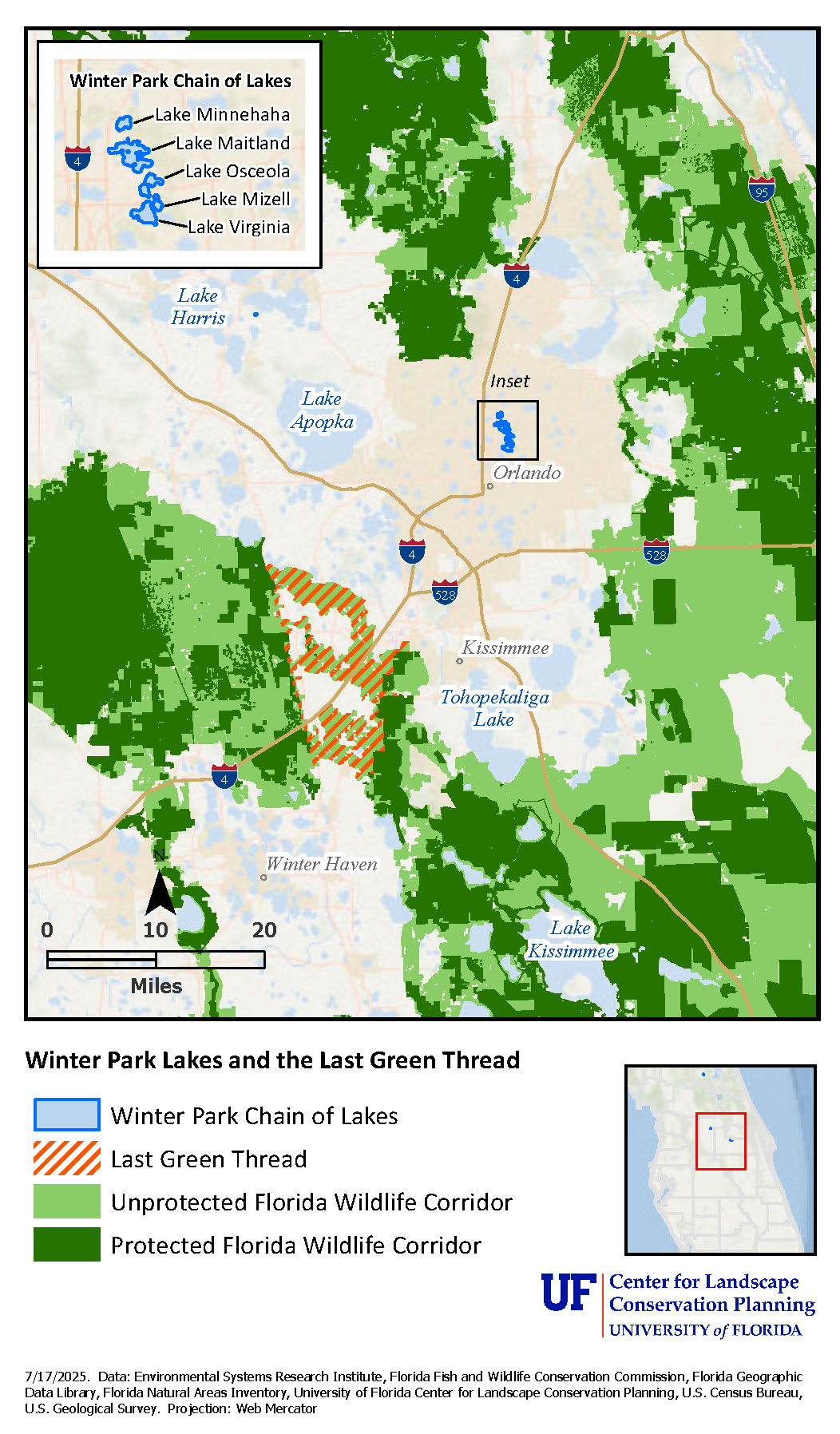

Map of Winter Park Lakes and the Last Green Thread

This area of Winter Park in central Florida is known for what conservationists call the “Last Green Thread,” a set of three linkages which are the last remaining connections within the Florida Wildlife Corridor between the Green Swamp to the north and the Kissimmee River watershed to the south. With eight million acres still unprotected, this is one of 10 critical linkages within the Florida Wildlife Corridor essential for maintaining a connected network of natural and rural landscapes.

Map of Lake Monroe, the St. Johns River, Contiguous Watersheds, and the Florida Wildlife Corridor

Since the 1840s, the cypress trees and wildlife on Lake Monroe in the Orlando metropolitan area have attracted visitors traveling along the St. Johns River. However, the region was occupied by indigenous Americans long before this period. The nineteenth-century painting in the exhibition likely references both the tourism industry and indigenous peoples. In the foreground of the painting, the landforms are evidence of the Enterprise midden left by early peoples; the house on the opposite shore references the contemporary business (or “enterprise”) bringing tourists and cargo alike on steamboats running along the river.

Wetlands

Florida wetlands take many forms, including coastal salt marshes in the north, mangrove swamps to the south, inland swamps, and the famed Everglades. These ecosystems differ in salinity, water retention, and vegetation, which contribute to their unique characteristics.

The Everglades dominate much of the artwork in this exhibition due to its significance during the period covered. Drainage efforts began in 1881 disrupting the water flow and ecology of the Everglades and weakening its future resilience to future changes including sea level rise. After years of additional alterations, the Everglades National Park was established in 1947 and today the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) to restore the Everglades is underway, with the participation of many government agencies and organizations to restore flows, improve water quality, and promote best management practices, including through land protection in the Everglades Headwaters north of Lake Okeechobee. Marjorie Stoneman Douglas’s famous book The Everglades: River of Grass (1947) describes our most iconic wetland as a “river of grass,” emphasizing its dynamic flowing water system. Wetlands like the Everglades play a vital role in supporting biodiversity, protecting coastlines during storms, sequestering carbon, and absorbing excess nutrients. They also provide habitat for numerous species of commercial, recreational, and ecological value. With the changing climate, coastal wetlands will need to migrate landward; however, this movement may be restricted by upland development.

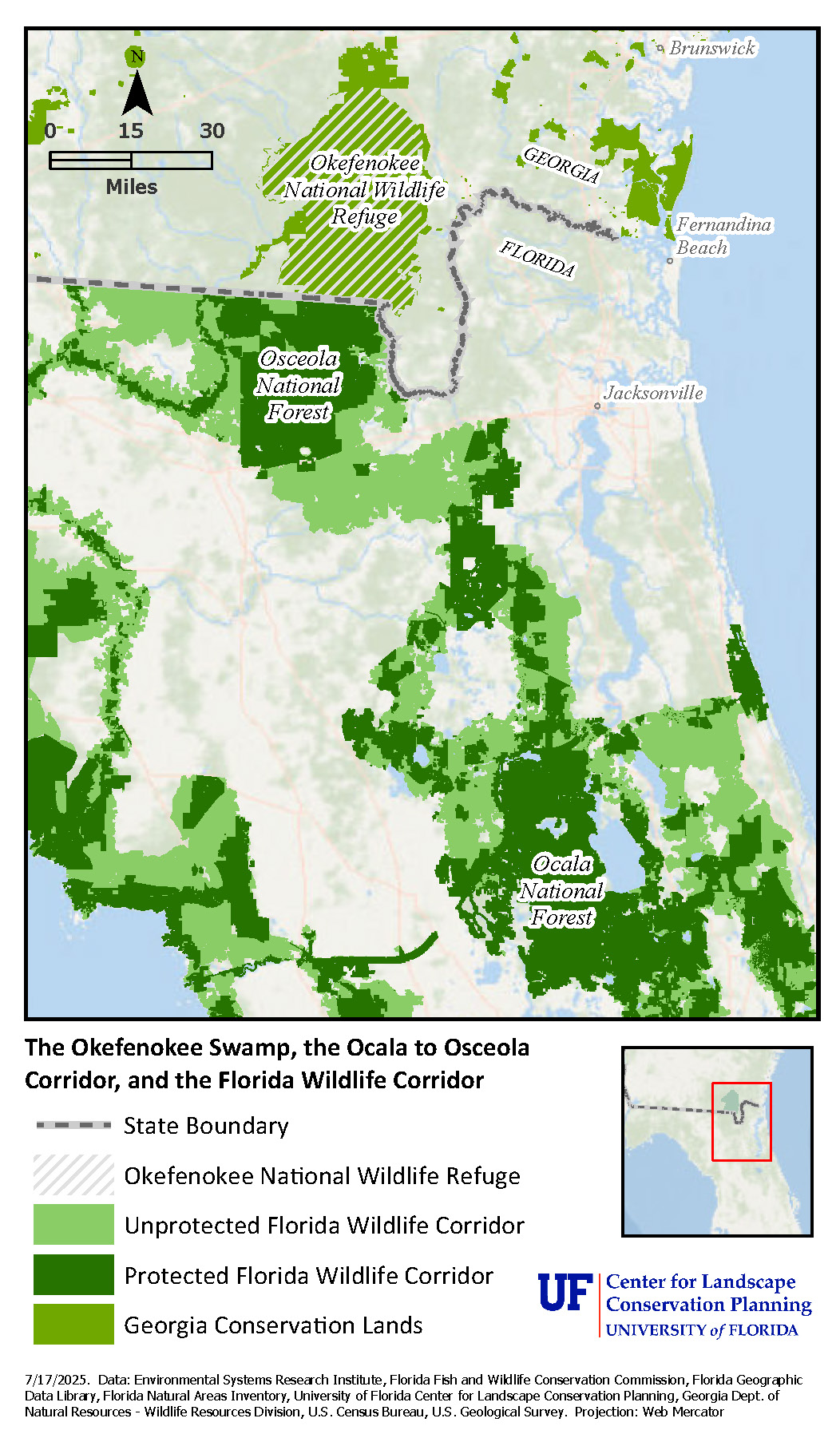

Map of the Okefenokee Swamp, the Osceola National Forest, and the Florida Wildlife Corridor

The exhibition painting depicts an eerie wetland in Georgia, now the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, which extends the Ocala to Osceola (O2O) Wildlife Corridor in Florida further north. This 100-mile section of the Florida Wildlife Corridor is a network of public and private lands connecting the Ocala and Osceola National Forests, a high conservation priority and essential for maintaining wildlife and water resources, working landscapes, military readiness, and south-north connectivity from Florida to Georgia.

Follow this link for a StoryMap of the Ocala to Osceola (O2O) Wildlife Corridor

Coast

Florida has 8,436 miles of coastline, the most extensive in the contiguous United States. The paintings selected for this exhibition portray the beauty and fragility of our coastline, as well as the keen interest in Florida’s beaches among visitors and potential patrons. This vast shoreline holds significant commercial value through tourism, seafood production, real estate, and recreation values, but it is equally important ecologically – and maintaining the ecology of Florida’s coasts is essential for protecting all of the other services that humans in Florida depend on. Florida’s coasts are diverse, featuring both high-energy Atlantic shorelines with dynamic beach and dune systems, and low-energy Gulf Coast areas – especially around the Big Bend – characterized by expansive coastal wetlands with innumerable channels and islands. These low-energy coastlines support salt marshes and mangroves that provide essential habitat, storm protection, and nutrient filtration services.

The variety of coastal landforms across the state contributes to Florida’s unique ecological richness. However, these coastal environments are highly vulnerable to climate change impacts, such as sea level rise, increasingly intense storms, and saltwater intrusion, as well as continued development pressure. Coastal wetlands and uplands are at particularly high risk, as their ability to migrate inland is often limited by urban expansion, seawalls, and roads. Recognizing these challenges, conservation and restoration efforts are critical to maintaining the ecological integrity of Florida’s coastline, and the variety of economic, recreational, and other values that it provides.

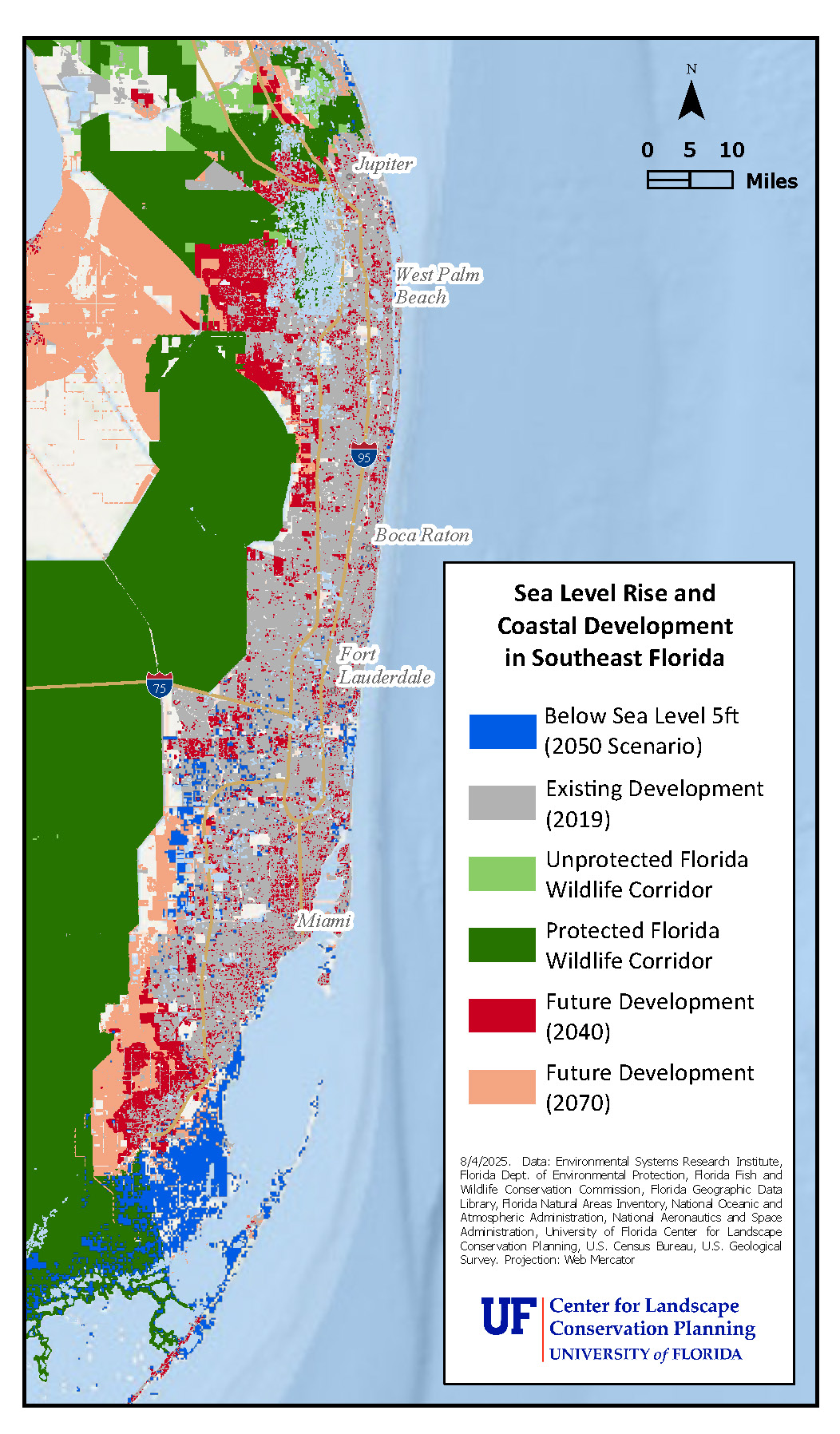

Map of Sea Level Rise and Coastal Development in Southeastern Florida

Florida’s coastlines continue to support important wetlands, dunes, and coastal forests providing critical habitat, storm protection, and other ecosystem services. However, these systems are increasingly squeezed between the “devil and the deep blue sea” as rising sea levels and storms increase erosion, and coastal development inhibits the ability for coastlines to shift inland.

This map depicts the combined threats from seal level rise and future development in southeast Florida. The love this artist feels for the ocean is evident in this exhibition painting depicting the coastal dune shoreline, a critical ecosystem at significant risk from both of these factors.

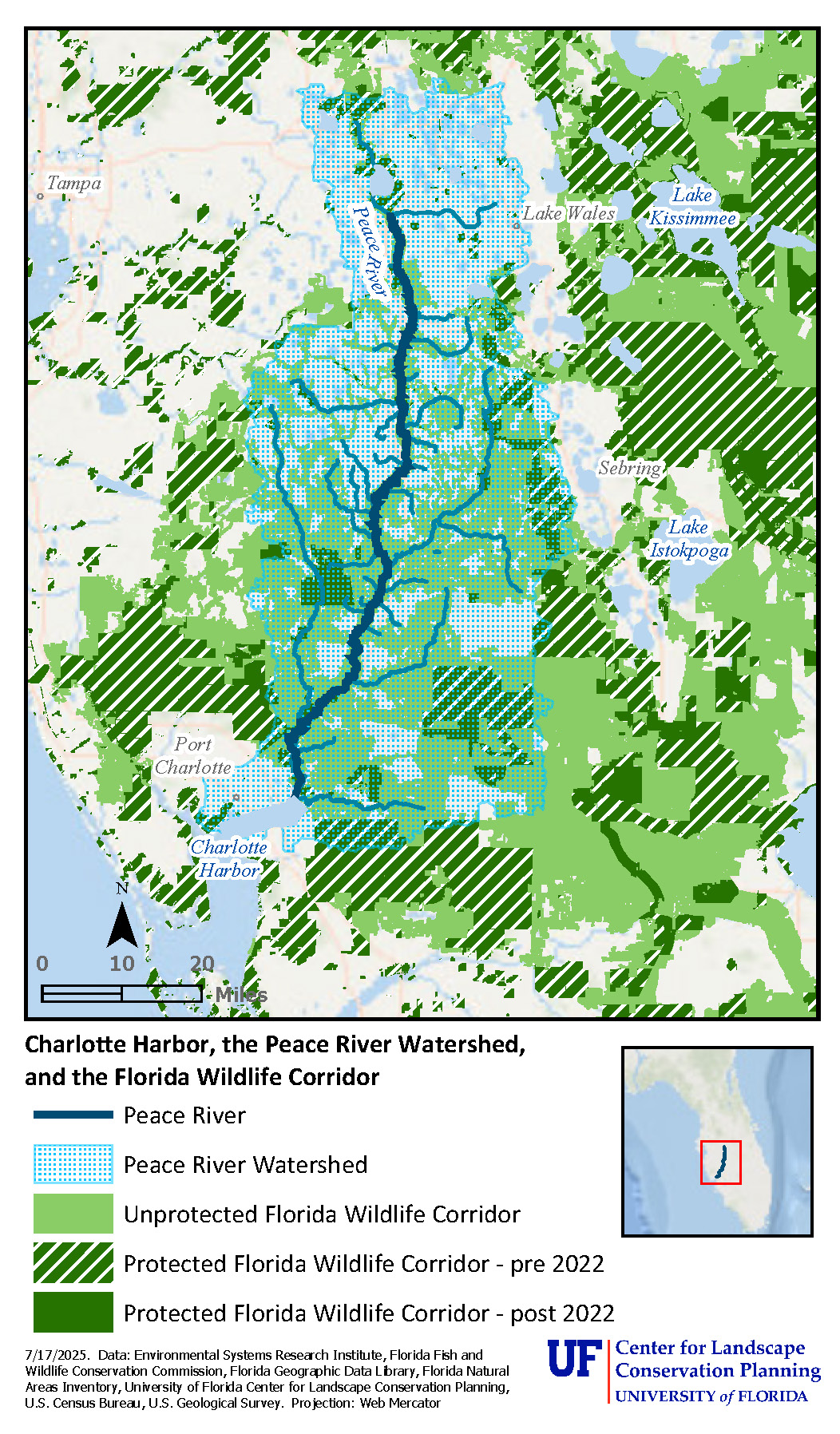

Map of Charlotte Harbor, the Peace River Watershed, and the Florida Wildlife Corridor

This map shows Charlotte Harbor amidst the Peace River Watershed and conserved landscapes in the area. In this exhibition painting we see the mouth of the Peace River, a designated Outstanding Florida Waterway, flowing through a landscape with critical ecological, hydrological, and economic significance. Yet it is one of the least protected watersheds in Florida. Center for Landscape Conservation Planning work with federal, state, and local partners including the Florida Conservation Group has led to the protection of more than 37,000 acres in this watershed alone since 2022 (as of July 2025).

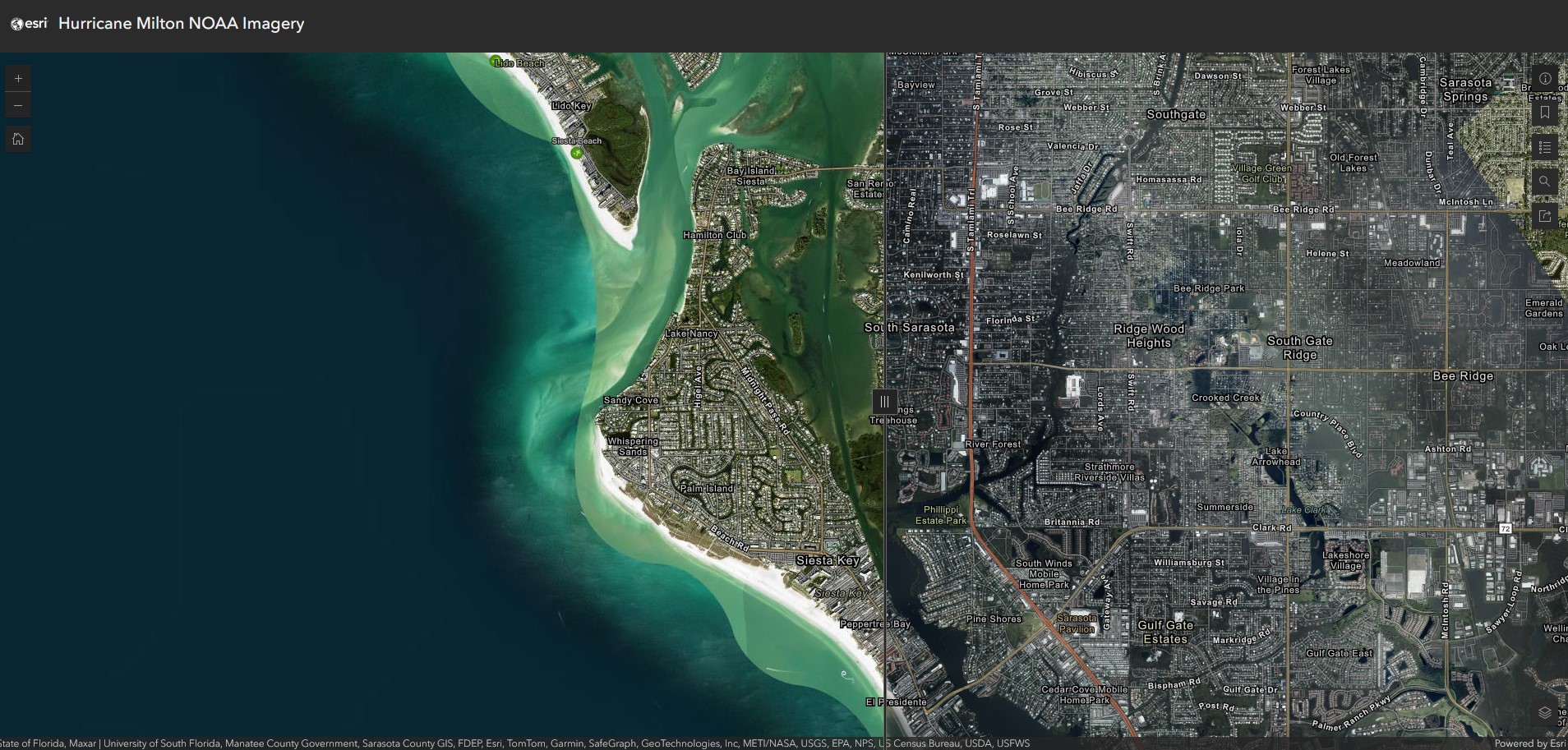

Pre- and Post- Hurricane Milton Aerial Imagery Viewer of Siesta Key from NOAA

The nineteenth-century view of Midnight Pass at Siesta Key included in the exhibition demonstrates the shifting nature of our coastline. A gradual accumulation of sand accelerated by storms, as well as human activity, closed this opening to the Gulf for roughly 40 years. Midnight Pass was reopened by hurricanes in 2024.

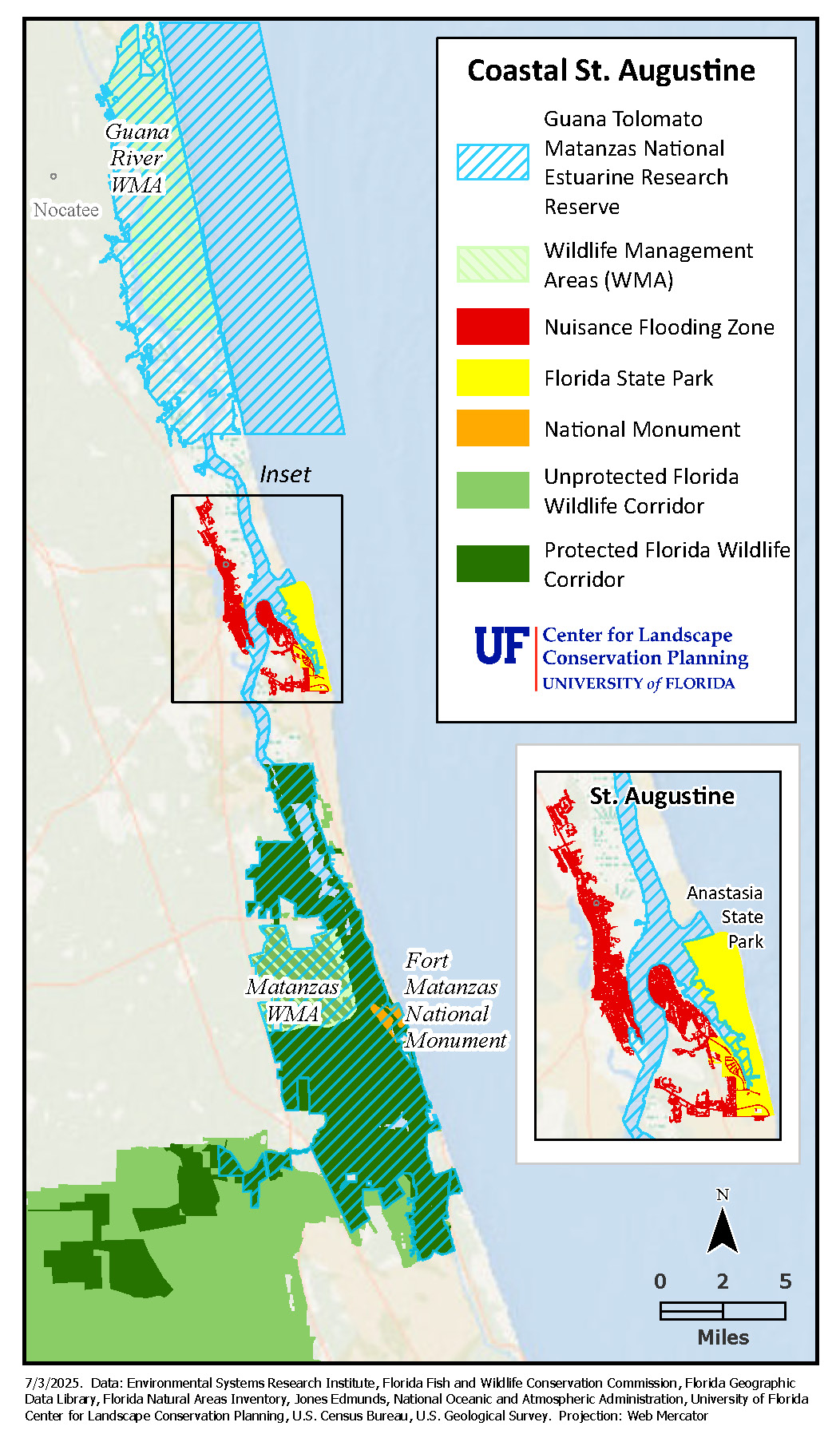

Map of Coastal St. Augustine with Matanzas National Estuarine Research Reserve, Anastasia Island State Park, and Nuisance Flood Zones

This region is critical for understanding the rationale behind landscape conservation, so several map elements are highlighted, corresponding to different paintings featured at the in-person exhibition. For example, the Matanzas River includes significant wetland ecosystems, recreational and boating opportunities, and historic resources such as the Fort Matanzas National Monument. Planning for future growth and change in this landscape will be essential to maintain these resources.

By the late 19th century, Anastasia Island, a barrier island east of St. Augustine, had become a popular tourist destination. Chartered boats offered access to the island’s beautiful beaches and lighthouse. In 1895, a new bridge from St. Augustine provided direct access for carriages to Anastasia Island. However, with access comes increased traffic. Today, the sole reason that Anastasia Island looks much like it did 150 years ago, is that the land was conserved as a State Park, underscoring the importance of protecting land to maintain both natural and cultural heritage for future generations.

The historic seawall, a painting of which is shown at the exhibition, has long been a central feature of life in St. Augustine. In addition to protecting the city against flooding from the Matanzas River, it has served as a place for scenic strolls along the water’s edge. The first seawall dates to the First Spanish Period and was constructed between 1695 and 1705. By 1821, the seawall had deteriorated significantly. Between 1833 and 1844, sections of the seawall were rebuilt and repairs continued through 1846 when a hurricane caused a portion of the wall to collapse. Today, the city has continued to maintain and reinforce seawalls, as a means of increasing resilience and protecting against future flooding.

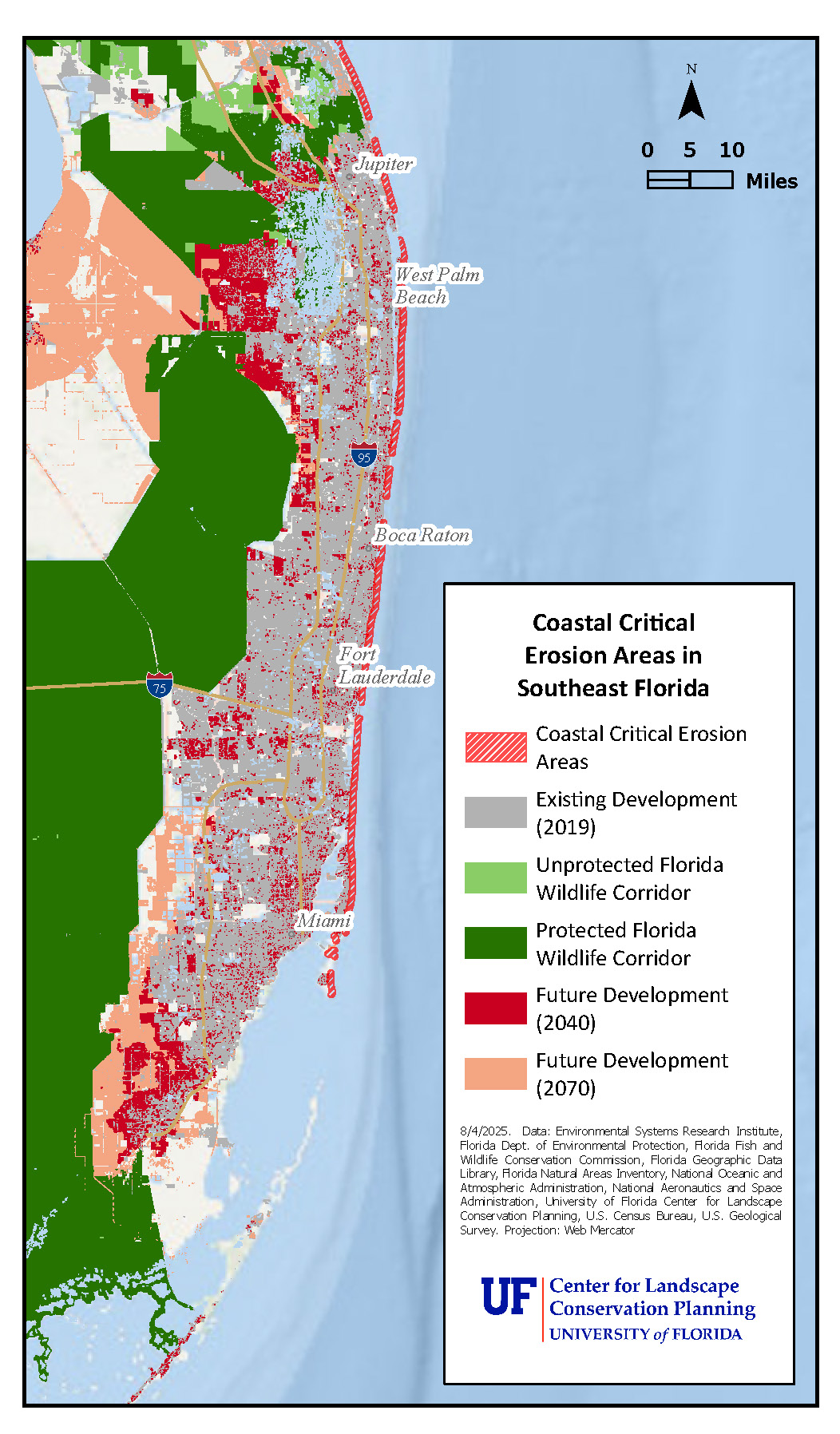

Map of Coastal Critical Erosion Areas in Southeast Florida

This exhibition painting highlights the importance of Florida’s coastline and beaches as tourist destinations in the early part of the 20th century, a role they continue to play today. However, Florida’s coastlines are increasingly at risk from coastal storms and sea level rise. This has required significant and sometimes short-lived investment in sand renourishment to maintain beaches in their historic locations, perpetuating the impression that Florida’s coastlines are unchanging.

In a painting at the in-person exhibition with a seemingly simple seascape with native mangroves, the artist depicts a coastal ecosystem most common in southern Florida that provides wildlife habitat, water filtration, shoreline stabilization, and coastal protection services. Planting mangroves along the shore in select locations is one way to increase resilience as climate change continues, but mangrove ecosystems are also threatened by coastal development and sea level rise.